GNU Guix: An Introduction

I have been going down the rabbit hole of functional package managers in the last few months and have nuked my system multiple times in the process. I started with NixOS, which I used for about a month until I decided to try out GNU Guix. And now my tower, my home server, and my laptop are running Guix System as their operating system, and guix is the primary package manager I use inside my wsl for work. This tool is excellent and drastically improved my Linux experience. In this blog post, I briefly overview GNU Guix and some of the basic features it provides.

What is GNU Guix?

GNU Guix is often described as an advanced package manager, but it is more of a universal software deployment system. You can imagine it as some deployment toolbox, which allows you to provide software and data like configuration files on your system based on a well-crafted plan. This plan is defined in Guile, a functional programming language based on Scheme. GNU Guix provides a variety of Guile modules, which allow you to define your system with expressive and composable building blocks. For your system configuration, you have access to a complete functional programming language with Guile; this allows you to structure and extend your configurations to support multiple systems of any complexity simultaneously.

The best way to think about GNU Guix is to see it as a package manager combined with features of Ansible and Docker. So, it allows you to install packages, create development environments, and create and deploy complete systems or clusters of systems.

How does GNU Guix work?

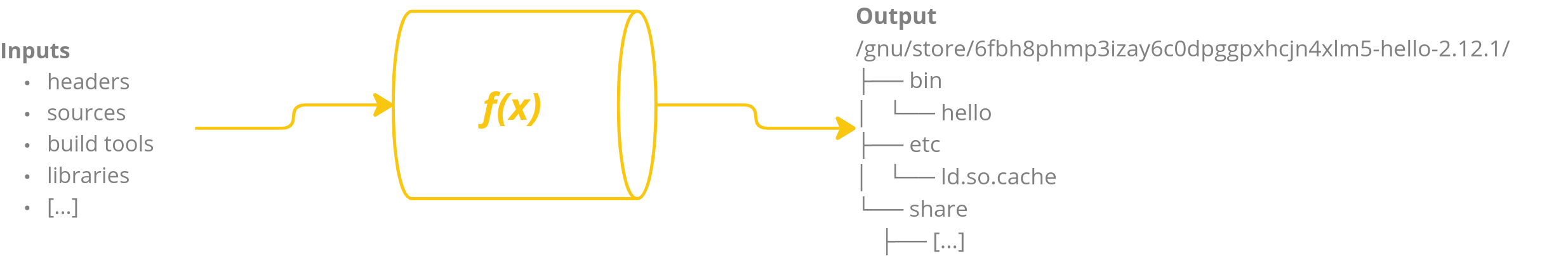

What makes GNU Guix special is the use of a purely functional approach for package management. This means the package build instructions are pure functions without side effects, called derivations. The packages themselves are the values of these functions. Derivations receive the dependencies as inputs. Using the same derivation with the same inputswill create the same packageevery time. If the inputs change (e.g., toolchain update or new library version), the derivations will create a different output value, which means a new package. Every package in GNU Guix is defined this way; this means each change on the system is detected, and everything that depends directly or indirectly on the change will reflect the change with a new package. So each system change is reflected as a unique system configuration.

Additionally, GNU Guix uses this unique configuration to provide multiple package versions. If you install software with GNU Guix, the software will be installed in the guix store under /gnu/store in a subdirectory named in the pattern: {unique_id}-{package_name}-{package_version}. The unique id represents a cryptographic hash of the package’s build dependency graph. So, each package will be installed in a unique directory based on its dependencies. This approach violates the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) but also enables a lot of the powerful features GNU Guix provides. With this approach, you can, for example, store multiple versions of the same package with all its dependencies, which will not interfere with each other. If you need different library versions, you can install them without destabilizing your system because each version and its dependencies are isolated.

With all packages stored in the guix store, we need another thing to make them available: profiles. A profile is a group of packages that will create a symlink tree. These symlinks will then be added to the environment variables like the PATH variable. With this approach, you can use the installed programs like usual. Each user can have multiple profiles; if no profile is defined, the default one will be used at ${HOME}/.guix-profile.

GNU Guix does not need to touch the root directory for this to work, which allows unprivileged package installation. Each user can install their favorite packages in the version they please. Only the packages of the active profile will appear in the user’s environment. So, each user can have their own set of packages, and what other users do with their profile will not affect them.

Installing GNU Guix

Enough theory. Let us look at how this works in action. First, we need to install GNU Guix. Many distributions already provide GNU Guix in their repositories so that you can install it as a typical package. Another possibility to install GNU Guix is with the provided install script. To use the install script, you need to execute the following commands1:

1

2

3

4

cd /tmp

wget https://git.savannah.gnu.org/cgit/guix.git/plain/etc/guix-install.sh

chmod +x guix-install.sh

sudo ./guix-install.sh

You should not run scripts from the internet as root on your device. You should check the script’s content first to ensure no harmful code is executed.

This command will download the installer script to /tmp and then run it as root. The script will then guide you through the installation. When the script is finished, you can run the following:

1

guix --version

If the version is printed out by guix, we can assume the installation succeeded. If this creates any errors, we may need to fix some configurations or install some packages. If you have such issues, you can check the GNU Guix Reference Manual for help.

GNU Guix as a package manager

With GNU Guix installed, we can look at some basic functionalities it provides. This post will focus on GNU Guix as a package manager. So, we focus on basic operations like installing and removing packages and some of the features that make GNU Guix special.

Install packages

The command to install packages with [GNU Guix] is guix install. So, if we want to install the package of GNU Hello, we can do so by executing the following:

1

guix install hello

The command

guix installis an alias forguix package --install(guix package -i).

After the installation, we can execute GNU Hello by running hello in the terminal. This command should print out a friendly greeting message. If the command is not found we need to source the profile. Sourcing the profile can be archived by executing the following:

1

2

GUIX_PROFILE="$HOME/.guix-profile"

. "$GUIX_PROFILE/etc/profile"

This command will set the environment variable GUIX_PROFILE and then source the profile environment. Alternatively, you can archive the same by executing:

1

guix package --search-paths -p "$HOME/.guix-profile"

So far, it is not much different from other package managers, so let us look closer. Generally, if we would install it with another package manager, we would assume that the binary is installed under /usr/bin, but if we search for the location of our binary with command -v hello, it says it is installed as $HOME/.guix-profile/bin/hello, but this is also not the actual location. If we list the binary with ls -l $(command -v hello), we see that this is only a symlink to: /gnu/store/6fbh8phmp3izay6c0dpggpxhcjn4xlm5-hello-2.12.1/bin/hello.

The install command has installed GNU Hello in the Store and updated the symlink tree in our default profile to map it in our environment. The Store path has the unique id 6fbh8phmp3izay6c0dpggpxhcjn4xlm5 on my system. When we look into the install directory in the Store, we see that this path only contains what the package provides. If we look at which shared objects are linked with ldd $(command -v hello), we get an output like this:

1

2

3

4

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffc81368000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /gnu/store/6ncav55lbk5kqvwwflrzcr41hp5jbq0c-gcc-11.3.0-lib/lib/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x00007fac27daf000)

libc.so.6 => /gnu/store/ln6hxqjvz6m9gdd9s97pivlqck7hzs99-glibc-2.35/lib/libc.so.6 (0x00007fac27bb3000)

/gnu/store/ln6hxqjvz6m9gdd9s97pivlqck7hzs99-glibc-2.35/lib/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fac27dcb000)

So not only GNU Hello is installed into the Store, but it also links against specific libraries that are stored therein isolation.

So, the installation has evaluated the Derivations of the GNU Hello package and defined the dependency graph. Then, all dependencies and our target program were installed in the Store under a unique path, and after this, a symlink to our hello executable was created in the default profile. The result is that only the program we want is provided in our environment, not the dependencies. Let us install an additional program that shows the benefit of this approach. We install cowsay with the following command:

1

guix install cowsay

After installation, the program cowsay will be available for our profile. You need to know that this program is a perl script. Each other package manager, the installation of cowsay, would also add the Perl interpreter to your environment. Still, if you try to execute this interpreter by running the perl command in the terminal, it will not find it. GNU Guix changes the link paths for binaries and the shebangs. So, let us look at what the file looks like. We can use the same method as we did for GNU Hello, but we can also ask [GNU Guix] directly with guix locate:

1

guix locate -u cowsay

After we have the location, we can show the shebang with head:

1

head -n 1 /gnu/store/v7amwlqxp3f5zzbypy9xzwhfdq3w86d7-cowsay-3.7.0/bin/cowsay

It shows that we do not see the usual #!/usr/bin/perl but also a path in the Store to the interpreter. That means if we installed a different version of perl in our profile, cowsay would not be affected because it uses his version. This approach brings an end to conflicts between system interpreters and development interpreters!

Remove packages

We installed cowsay only to show the shebang changes, so we can now remove it again. To remove a package in GNU Guix, we can invoke guix remove:

1

guix remove cowsay

The command

guix removeis an alias forguix package --remove(guix package -r).

So now cowsay is no longer part of our environment. But running guix locate cowsay shows that the program is still available in the Store. So what happened? The command guix remove only removes the package from the profile, so the symlinks no longer exist, but the command does not touch the Store. We have not removed a package, we generated a new generation of our package list. A generation is a set of packages installed on the system in a specific configuration. We can show the generations on the system by executing:

1

guix package --list-generations

The command generates an output similar to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Generation 1 Jan 28 2024 19:12:16

+ hello 2.12.1 out /gnu/store/6fbh8phmp3izay6c0dpggpxhcjn4xlm5-hello-2.12.1

Generation 2 Jan 28 2024 19:12:22

+ cowsay 3.7.0 out /gnu/store/v7amwlqxp3f5zzbypy9xzwhfdq3w86d7-cowsay-3.7.0

Generation 3 Jan 28 2024 19:12:28 (current)

- cowsay 3.7.0 out /gnu/store/v7amwlqxp3f5zzbypy9xzwhfdq3w86d7-cowsay-3.7.0

You can switch between all existing generations if you want. Let’s say we want to have cowsay back. We can call:

1

guix package --roll-back

This command changes our current generation to the previous one. So, we are now at the state where cowsays was freshly installed and can execute cowsay again. We can switch to every generation we want, so if we want to go to our 3rd generation, we can do this by invoking the following:

1

guix package --switch-generation=3

Generations reflect every change in the package list, including updates. If you have an update that has broken something in your workflow, you can switch back to the generation where everything worked. This approach makes it hard to break your system!

If you want to remove packages from the Store, you can do so with guix gc; this command invokes the garbage-collector. It will remove all packages not belonging to a profile generation and allow you to delete generations based on patterns.

Update packages

I already mentioned updates. Let’s look at how updates are done in GNU Guix. If we want to update our packages with GNU Guix, we need to update our deviations first, and then we can update our installed packages.

A collection of derivations is called channel. To update our channels, we need to invoke guix pull. This command will download the new derivations and update the guix cli tools directly. The tools will be built from scratch, which could take some time, but this ensures that the tools and derivations are always in sync.

After the channels are updated, we can update our packages by invoking:

1

guix upgrade

The command

guix upgradeis an alias forguix package --upgrade(guix package -u).

This command will first update the packages in the current profile by installing them in the Store. When all packages are updated this way, it will create a new generation. After the generation, it will create a symlink that replaces ~/.guix-profile. This means the last step is only the generation of symlinks. Symlinks have a considerable benefit: creating symlinks on Linux is an atomic operation. So, when the current profile is changed, the update is complete, which allows transactional updates. The current profile will remain the same if anything happens before this step is completed. So you can cancel the update anytime, and your system will stay in a well-defined state!

Search packages

We talked about how we can install, remove, and update packages. This is all great, but you can only do it if you know which packages exit. So let us talk about how we can find the packages we want. If we would, for example, search for the binary data editor GNU poke, we can search for the program by executing the following:

1

guix search poke

The command

guix searchis an alias forguix package --search(guix package -s).

This command gives a list of packages that match our search pattern. The output provides us with a lot of information about the program, such as a description, the needed dependencies, the program’s license, and the location of the derivation function. Sometimes, this information is unnecessary, and we only want to know the package’s name for a program we already know. In this case, we can search in the available derivation with:

1

guix package --list-available=poke

The command

--list-availablecan also be shortened to-A:guix package -A poke.

This command also provides a list of matching packages but only minimal information like the location. So now that we know the package name, we can install it with guix install poke. But with the name, we can also use some additional tools provided by GNU Guix. If we want to know how, for example, the package is built, we can open the derivation directly in an editor with:

1

guix edit poke

This command will directly open the default editor (based on the EDITOR environment variable) on the derivation definition. If you want to see the dependency graph of the package, you can also create the graph of the derivation with:

1

guix graph poke | xdot

The command will directly open xdot, showing the dependency graph. The tool guix graph will generate a graph in the xdot-format, so we can also use the Graphviz to create various image formats out of it. If we want to create an svg-image, we can invoke:

1

guix graph poke | dot -Tsvg > poke_graph.svg

Summary

In this post, we discussed the basics of what GNU Guix is and how it works. We also looked at using some package manager features of GNU Guix, describing how to install, remove, update, and search for packages. On the way, we also teased some additional features of GNU Guix and tried to highlight some of the benefits this tool provides.

This post only introduced the basics and focused mainly on the guix package command. GNU Guix provides more features than this command alone. We did not touch on the possibilities for reproducibility GNU Guix provides. We also did not take about guix home, where we can define not only our packages but also our home configurations, or guix shell and guix build, which provide a ton of possibilities for reproducible software environments, continuous integration, and continuous deployment.

GNU Guix changed the way I use my computers a lot, and if you give it a try, it will improve your experience with GNU Systems as well.

References

Websites

Papers

- Eelco Dolstra 2006: “The Purely Functional Software Deployment Model”

- Ludovic Courtès 2013: “Functional Package Management with Guix”

Footnotes

You can find detailed install instructions in the GNU Guix Reference Manual ↩